Still burning bankers after 700 years? RIP Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Templars

Given that the bottom nearly dropped out of the financial world with the subprime lending catastrophe, what would it take for Western civilisation to lose faith in free market economics? If the banking system were deemed no longer fit for purpose what would we do with the monumental fall-out other than ‘build a bonfire, build a bonfire, and put the bankers on the top’? It seems fair to hold the money men and women to account for our enduring financial crisis. But we might just want to spend a moment in reflection upon this 700th anniversary of the death of Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Knights Templar.

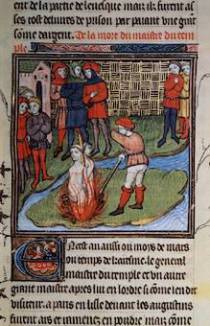

On 18th March 1314 De Molay and his fellow leader, Geoffrey de Charnay, reneged on the confessions of heresy which had been extracted from them by torture. After almost seven years of incarceration, on an islet in the River Seine, a stone’s throw away from Philippe IV’s royal palace, they were slowly roasted alive. But how did the Order of the Temple, which in the space of two centuries had become such a powerful institution, meet with such a swift and spectacular downfall? It all started with aspiration.

The dream of possessing the ‘Kingdom of Jerusalem’, God’s own country, was embraced by poor and rich alike. Some ‘took the cross’ and joined in the violent land grab of the ‘Holy Land’, gaining full remission from time in Purgatory - the medieval equivalent of retiring on a full pension. Many others financially supported the sacred mission of the ‘Crusades’, by buying indulgences. Indulgences were a type of insurance policy, paid via the brokers of the Church. An indulgence bought the peace of mind that the investor and their relatives would one day dwell in paradise. The faithful were desperate to buy into the promise of eternal real estate.

A third type of spiritual investment for Christians across medieval Europe was to endow the various orders of soldier-monks. In addition to substantial land-holdings from such endowments, the Templars amassed immense liquid assets from their main enterprise of protecting pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. These financial holdings, unique to the Templars, enabled them over the years to act as a lending bank. But then, the crash came, at a time when the political climate was changing: the nation state was expanding and the heavenly state was diminishing. It was the beginning of the end for the soldier-bankers.

The crash happened in May of 1291 when the port of Acre fell. Christendom lost its last toehold in the ‘Holy Land’, and the Templars simultaneously lost their raison d’être. There was widespread spiritual angst that the investments of European Christians had been squandered. Now the stage was set for Philippe IV of France, who was well ahead of the game, to act. With no territory left on earth for the Templars to defend, they made obvious scapegoats for the collapse of the medieval dream, and Philippe could cash in. It was an insightful manoeuvre to set up Jacques de Molay, his knights and brothers as usurers, heretics and blasphemers, whose wickedness had caused the loss of the promised land, and with it the future prospects of good Christian folk.

As we commemorate the setting light to the faggots beneath the Templar bankers who took the blame for the crash (and ironically they were somewhat culpable), it is worth taking stock. With the Crusades, it was the ordinary faithful folk whose desire for eternal security was stoked and poked, who bought into the dream of heaven on earth. They maxed out their investment. And before we dismiss them as fools, consider whether the post-modern person in the street has something in common with the medieval man in the mud-track: we have been prepared to lay our hard-earned cash at the feet of anyone who persuades us that they can give us our heart’s desires. Yet in the first place these desires are fed to us and inflamed by the same money-making machine.

If we are to learn anything from this tragic Templar tale, perhaps we need to put ourselves to the question: What dream have we bought into? Has the crusading spirit of free market capitalism succeeded in establishing our security? If not, then maybe instead of building a bonfire and putting the bankers on the top, we should take responsibility for ourselves and put our faith in a different socio-economic worldview - before it is too late and the final crash comes.

The last word must go to the Grand Master who suffered that gruesome death 700 years ago today. From his pyre he cursed his accusers. King Philippe IV was dead within the year, as was Pope Clement V who stood by and let it all happen.

Jacques de Molay and Geoffrey de Charnay, RIP.